Latin America’s violent crime problem

Despite years of economic growth Latin American crime levels continue to rise. LatAm INVESTOR takes a look at what's behind the problem...

What has happened?

A new UN report has just confirmed what many suspected – that Latin America is one of the most violent places on earth. Analysing crime data between 2001 and 2011, the report found that the murder rate grew by 12% across Latin America. Theft is also up, with the rate of robberies tripling in the last 25 years. The increase in crime is particularly marked because it comes at a time when crime is falling or stabilising in the rest of the world. It also comes at a time of unheralded prosperity in the region, which has enjoyed solid economic growth over the period.

Hotspots of violence

Generalisations are always dangerous and, when it comes to Latin American crime, there are big differences between countries. On one end of the scale there are the Honduras, El Salvador, Venezuela and Belize, which have the unhappy honour of being four of the world’s five most violent countries. On the other end you have Uruguay, Chile and Costa Rica, which are relative beacons of safety in the region. Some countries, such as Colombia or Guatemala, still have relatively high homicide rates but have seen massive improvements in the last few years. Contrast also exists within the same countries, explains Heraldo Muñoz, the Assistant Secretary General of the UN. “Some municipalities, states or departments show indicators comparable to those of European nations but in others lethal violence is even greater than in countries at war". “Some municipalities, states or departments show indicators comparable to those of European nations but in others lethal violence is even greater than in countries at war".

Are economic factors to blame?

One reason could be that the fruits of Latin America’s recent economic boom have not been distributed equally. The Gini coefficient, which measures income inequality, currently stands at 0.5 in Latin America. That’s a slight improvement from the 0.54 it measured in 2000 but it still makes Latin America one of the most unequal places in the world. Europe, North America, Asia and even North Africa, have fairer income distribution. One reason for this is the conservative nature of many Latin American economies, where traditional family-owned conglomerates control large swathes of the economy. Yet with many countries opening up their economies this may change. Regressive tax systems, that placed an emphasis on middle-class benefits such as public universities, are also being made more progressive in many Latin American countries. All of which suggests that wealth distribution in the region may become more equal.

What about the state?

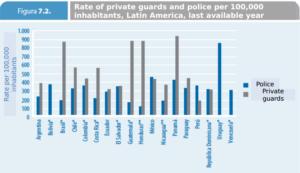

Weak institutions have played a large role in the crime crisis. The UN’s report highlights “the lack of capacity of the state—police forces, judges, prosecutors, and prisons—to adequately address security challenges.” Local police forces, which are often corrupt or incompetent, are a big problem. “The police force, as the most visible face of the State, is amongst the least valued institutions with the lowest levels of confidence among Latin America’s youth”“The police force, as the most visible face of the State, is amongst the least valued institutions with the lowest levels of confidence among Latin America’s youth”, says the UN. Indeed a UN survey found that in only Chile, Brazil, Panama and Nicaragua, did at least 50% of the population see the police as a force for good. As a result many have turned to private security, and Latin America now has more security guards than police officers. Things are just as bad in the judiciary, where cases are often delayed for years and the standard of prosecutors is poor. Widespread corruption means that many victims of crime don’t bother taking their case to court if they know that the suspect can afford to bribe the judge. The final, and perhaps weakest, link in this chain is the prison system. “The penitentiary system is in crisis in virtually all countries in the region”, says the UN. “Overpopulation and issues of pre-trial detention are the clearest symptoms of this crisis.”“The penitentiary system is in crisis in virtually all countries in the region”, says the UN. “Overpopulation and issues of pre-trial detention are the clearest symptoms of this crisis.” Voters that are, understandably, worried by the insecurity often vote for politicians that promise ‘mano dura’ (iron fist) policing strategies. But these place more pressure on a crumbling prison system.

What about drugs?

Of course the elephant in the room of any discussion of Latin American crime is the region’s involvement in illegal drug production and trafficking. Money from the cocaine trade has helped to fuel the Farc’s Colombia insurgency, one of the longest-running in the world, while dangerous cartels battle over drug shipment routes in Central America and Mexico. Over the last ten years we have seen a range of policy approaches, none of which have been very successful. Ex Mexican president, Felipe Calderon, tried to take on the cartels with the army, but the bitter confrontation caused the murder rate to rocket. Other countries have effectively decided to turn a blind eye to drug gangs. That keeps the homicide rate down but weakens the power of the state’s institutions. Any real solution must include the consumer countries in North America and the EU. The high price their citizens are willing to pay for drugs offers a powerful economic incentive and makes it unlikely that any Latin American policing tactic will ever be able to stop the trade. Ultimately the solution may lie in legalisation in the West – a point that several Latin American presidents have started to make in recent years.

How does it affect investors?

Many firms in Latin America don’t have any involvement in crime. However, for those unlucky enough to be in one of the hotspots, it becomes a serious issue. As Luke Smolinski notes in the FT, “the lawlessness has raised the cost for business. Firms must pay for insurance, private security and crime prevention.” Moreover, extortion means that firms often try to hide their earnings, which means they will often make do with older, cheaper equipment – and that affects productivity. The atmosphere of fear often puts off consumers too. UN surveys have found that, depending on the country, between 45% to 65% of people have stopped going out in the evening for fear of crime. That’s bad news if for restaurants and bars. The overall cost of this crime on the economy is hard to calculate but a joint report from the International Development Bank and the UN, estimates that on the extreme end, in countries like Honduras, it can cost up to 10% of GDP, while in more peaceful places like Uruguay it is nearer to 3%. There are also wider costs. More than 1million Latin Americans have been killed by violent crime in the last decade, while the hundreds of thousands that belong to the region’s worst gangs are effectively prevented from having a normal life.

But the crime problems have also created investment opportunities. British firms have been doing good business selling equipment to police forces across Latin America. There has also been a boom for private security firms who now employ more than 3 million people across the region. Moves to improve the prison system may see more opportunities open up for outsourcing companies. Local entrepreneurs in places like Mexico and Colombia have also been quick to react and created custom services in armoured cars and bullet-proof children’s school bags.