Amlo Fears Debt More Than Coronavirus

Amlo's austerity continues in Mexico's 2021 budget, with frugal public spending despite the worst economic contraction in living memory. We investigate if the country is heading for another debt crisis...

The third in a series of articles that explores if Latin America is heading for a debt crisis...

If any country should be worried about another lost decade it is Mexico. It was the epicentre of the 1982 debt crisis when it halted repayments on its $82billion debt, which was the second-largest in the world at the time. Today there are worrying parallels. Yet again Mexico’s debt is worth 50% of GDP, while its main trading partner the US, whose interest rate rise sparked the last crisis, is once again in deep economic trouble. And just like in the 1980s the oil price has collapsed – black gold abandoning Mexico when it most needs the export revenues.

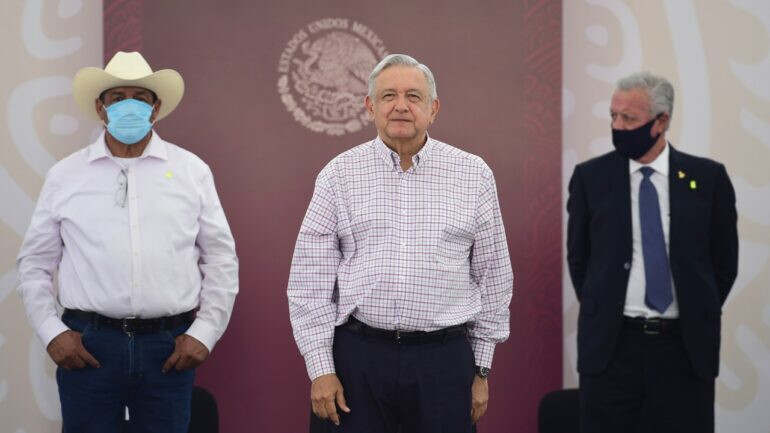

It’s little wonder then that president Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, or Amlo, is loath to add more debt. The left-wing populist surprised many with his austere public finances since taking office in 2018. Even more surprising is that he hasn’t changed course during the pandemic. Mexico’s coronavirus relief package of fiscal measures was the smallest of any major Latin American economy, worth just 1.2% of GDP. An old-school economic nationalist, Amlo is leary of increasing Mexico’s dependence on international investors.

Amlo’s fiscal discipline deserves praise, it ensured that Mexico entered the crisis in better shape than the likes of Brazil, Argentina or Ecuador. But the problem is that Mexico’s economy was unwell before the pandemic hit. It grew 0% last year as the new president struggled to deal with the age-old problems of patchy productivity, corruption and violence. Indeed, his efforts to sabotage Mexico’s largest investment project, the new airport, and reverse its energy reform probably made things worse. In the same way that Covid-19 is most dangerous for patients with a pre-existing condition, it really hurts economies that were already weak. As a result, Mexico’s GDP is expected to contract by 10.4% this year – the worst recession for any emerging market in the world.

Oil problems

Mexico has the most diversified economy in Latin America. It’s an industrial powerhouse, with world-class factories in the northern states that are integrated to US supply chains. But it also has strong commodity exports and tourism sector. Diversification is meant to help you in times of crisis, but unfortunately for Mexico it’s taking a hit on multiple fronts. Tourism, which accounts for 7.5% of GDP - the highest in Latin America, has been paralysed by Covid-19. Then there is oil and gas. Mexico isn’t as reliant on oil as it was in 1982, but nonetheless the recent collapse in prices reduced export earnings.

"Amlo’s fiscal discipline deserves praise, it ensured that Mexico entered the crisis in better shape than the likes of Brazil, Argentina or Ecuador…"

That collapse in the oil price is particularly relevant for Mexico’s public finances. The last administration of Enrique Peña Nieto passed a historic energy reform that opened up Mexico’s hitherto state-dominated oil and gas sector to private investors. There were many reasons for the reform but one of the most important was that Mexico has so much hydrocarbons that it was impossible for national oil company, Pemex, to develop the resources to their full potential. A fact that is demonstrated by the alarming decline in Mexican oil production over the last decade. Indeed, Pemex’s attempt to develop these resources have seen it rack up more than $100billion of external debt.

As UK-based consultancy Capital Economics points out “if the firm were private, it would be difficult to avoid a default.” But Pemex can keep borrowing because the market assumes it would be bailed out by the Mexican government – especially one that is led by a resource nationalist like Amlo. So, Pemex’s debt woes are Mexico’s debt woes and while the firm’s borrowings aren’t reflected in the official debt-to-GDP figures they represent a financial burden for the state. So, the current low oil price is dangerous, not just because of the hit to export revenues but because of the pressure it puts on Pemex’s debt.

Factory failure

Then you have Mexico’s industrial sector, which is normally the bedrock of its economy. Mexico exports as much manufactured goods as the rest of Latin America combined – an incredible statistic that shows how far its factories have come since the 1994 signing of Nafta opened up access to the US. But with America suffering the worst coronavirus outbreak in the world – in terms of total deaths – and a second wave (or delayed first wave) of infections that has sent many southern states back into lockdown, Mexican production has collapsed. What will really worry Amlo is that there is little sign of a recovery. As IHS Markit explained in our latest issue, other large Latin American economies like Colombia or Brazil, suffered an industrial downturn in April but recovered in June and July. But Mexico’s Manufacturing PMI score of 40 in July shows that the sector continues to contract.

Put simply Mexico is suffering one of the world’s worse coronavirus recessions and the economy doesn’t look like recovering quickly. Or as Capital Economic’s Nikhil Sanghani explains in more detail: “Overall, the large hit to the economy and a weak recovery means we expect a larger than-consensus 10.5% contraction in Mexico’s GDP this year. And we think that the levelof GDP will be around 7% below its pre-virus trend by the end of 2022, one of the largest gaps in the emerging world.”

Amlo is in a difficult situation. Public debt is forecast to reach 65% of GDP by 2024 unless he returns to austerity, yet cutting state spending will further delay the economy. But for all the pessimism there are still grounds for optimism. A US spending splurge before the election could give Mexico’s factories an unexpected boost in the short-term. While longer-term, Mexico’s real structural challenges are not coronavirus related. If Amlo can reduce violence and corruption or boost productivity in the southern states then Mexico could still surprise the analysts. It’s worth remembering that Mexico was the first major Latin American economy to recover from the lost decade. It pioneered debt relief with the Brady Bonds in 1989 and in 2003 became the first country in the region to retire those bonds. The debt crisis of the 1980s led to liberalisation of the economy in the 1990s, culminating in the free trade deal with the US and Canada. Hopefully the current economic crisis will encourage Mexico to tackle some of its long-standing structural flaws.