Brazil at economic crossroads with Lula v Bolsonaro

Adam Patterson, our correspondent in Curitiba, explores what the presidential elections hold for the Brazilian economy…

The philosopher Camus famously compared modern life with Sisyphus, a figure of Greek mythology who, punished by Zeus, was forced to roll a boulder up a mountain for eternity. Every time it nears the top, the boulder rolls back down. That´s a useful analogy to understand the Brazilian economy over the last few decades.

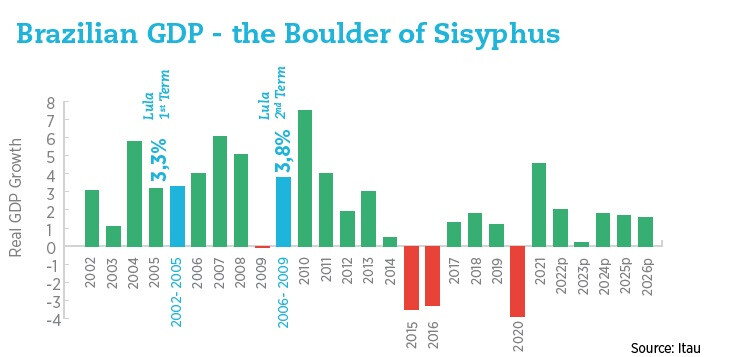

The Plano Real of the 1990s set the scene for a structural recovery of the Brazilian economy and currency afflicted by years of stagflation and economic crises after the “economic miracle” of the military government in the 1960´s and 1970´s. The trade union workers activist, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, or ‘Lula’, won the election in 2002 for the Worker’s Party [PT in the Portuguese abbreviation] promising progressive economic policy. It was similar to 1990’s Blairian discourse in the UK and, just as New Labour continued the pro-market economic guidelines of the previous government, so Lula followed the course of respected President Fernando Henrique Cardoso (FHC), during his first term. The economy boomed, riding a super commodity wave, expanded exports to China and a cheap credit bubble.

The Economist´s iconic front page in 2009 with a rocket – “Brazil takes off!” - perfectly encapsulated the positive sentiment. The boulder was seemingly getting to the top again. GDP growth hit 7.5% in 2010. But Lula´s second term from 2006, increasingly borrowed from the typical Latin American socialist playbook with greater state intervention and public spending. From 2001 to 2015, primary expenditures grew by a staggering 460% and 200,000 public sector workers were added to the state payroll.

By 2016, fourteen years of Worker Party rule ended with the country´s deepest recession on record, a massive corruption scandal and the impeachment of Lula’s handpicked successor, Dilma Rousseff who was finally brought down by unconstitutional fiscal maneuverers and huge street protests. GDP fell by more than 7%. The ensuing institutional crisis eventually led to President Bolsonaro´s unexpected win in October 2018 with a firm mandate to end corruption, reform the economy - steering it to a more free-market paradigm – and implement popular pro-family and law and order policies.

Bolsonaro’s Brazil

And yet the Brazilian economic boulder is especially hard to manoeuvre. The chronic economic mismanagement of PT also left a deep hangover. During Bolsonaro´s first year in 2019, GDP grew by just 1.2%. The administration found it hard to pass the much-heralded macro-economic reforms and privatizations, which Bolsonaro had been elected to implement, though Congress and against opposition from the left-leaning activist Supreme Court. Indeed, after four years of Bolsonaro, Brazil still has a whopping 400 state-owned enterprises.

Then Covid hit. Brazil´s economy proved more resilient than most developed countries, with a downtick of 3.9% against 6.8% in the Euro-area, helped in part by one of the worlds’ most ambitious fiscal and monetary support packages. Moreover, the approval of pension reform in 2019 – R$800 billion in savings over ten years - was a major victory for the President after decades of failed attempts. The public debt trajectory became more sustainable.

Record infrastructure delivery and PPP concessions also provided significant wins. Nonetheless, the macroeconomic holy grails of much needed administrative and tax reform - barred by the Senate - and an extensive privatization programme remained out of reach. For Mauro Schneider, an economist at Brazilian consultancy MCM Consultores: “the public spending debate has advanced very little”.

However, even with global headwinds, the Brazilian economy is seemingly on a positive track, with GDP projected at 2% this year and inflation trending down, potentially below US and European levels, helped in part by the federal Government´s huge petrol, energy and import tax reductions. Employment is at is highest in a decade and FDI doubled in 2021, while corruption is much reduced.

Lula v Bolsonaro

Overall, looking towards the October presidential elections, the author would contend that the business community prefers a Bolsonaro win over Lula. The latter is eligible after the Supreme Court, mostly filled with judges appointed by PT, squashed – on a technicality – Lula´s prison sentence for corruption. Tellingly, when this was announced in 2021, the Bovespa fell 4%.

Current polls suggest a two-horse race. In business circles, the parallels are often made with Joe Biden succeeding Donald Trump in the US. Capital flight could follow a Lula victory.

Alessandra Ribeiro, managing partner of macroeconomics at Tendências Consultoria agrees that business leaders “prefer Bolsonaro as the market bet a lot on the President and bought his [liberal] agenda but that some of his policies have not been well received such as price intervention and in the conduct of state-owned companies”. Not to mention, an emergency law – sanctioned by Congress - increasing government spending above legal thresholds (the so-called “fiscal-roof”) in the run-up to the election, justified on the grounds of extraordinary inflationary pressures.

The consensus seems to be that a Bolsonaro second term could see continued incremental macroeconomic progress or, depending on the composition of congress post-election a renewed push for historically-necessary reforms. Indeed, Finance Minister Guedes sums up his objectives as “major reforms, maintaining social spending and ending institutional privileges”.

And what’s the market’s take on Lula? The answer depends on “which” Lula to expect in 2022. Lula was a trade union agitator in the 80s and early 90s – borrowing again from UK politics, a type of Arthur Scargill – who ran and lost three times for the Presidency in 1989, 1994 and 1998 before finally winning in 2002 after his “letter to the Brazilian people” stating that he would follow the parameters of the FHC government, reassured the markets. In his first term – in which he inherited a large primary surplus and low public debt dynamics - he did follow the Plano Real “macroeconomic tripod”, with a floating exchange rate, inflation targeting and spending limits. This pragmatist economic policy changed drastically in his second mandate from 2006 with greater state intervention and fiscal expansion.

Signs are emerging of which Lula the market can expect in 2022, even though the 76-year-old has been coy around the fine points. He has argued that a way to fix Brazil’s problems is to “put the poor in the budget” and “tax the rich”, prioritising battling “inequality” rather than fiscal rules. Essentially, PT’s economic policy is focused on public expenditure, big government and activist state-owned companies like Petrobras. Not to mention, reviewing the 2017 labour reforms and privatization efforts.

This worries the market as such a platform is certain to repeat past mistakes and ramp up already worrying government debt levels. Lula has also recently called for increased press regulation, progressive law and order policies and supported attacks on private property. For these reasons the influential Antagonista political website contended that “replacing Jair Bolsonaro with Lula is dangerous for Brazilian democracy”. Even an article on liberal CNN argued that “Lula does not point to the future, but to a revisionism of the past”.

Lula is leading the polls, but many believe they overestimate his support whilst underestimating Bolsonaro´s. Famously, Lula does few public events so as not to be booed whilst the President draws large crowds. Time will tell. As always, what´s important for the market is the discourse and policies of the candidate, rather than who wins per se. Nevertheless, for economic “order and progress”, the business community expects continued adherence to fiscal spending limits, privatization initiatives and most importantly tax and administrative reform to ensure the economic boulder moves onwards and upwards. As it stands, the consensus seems to indicate that a Bolsonaro government is more likely to deliver these goals.