Latin America in 2024

The stable economic outlook is offset by a complex risk landscape, writes Gavin Strong, Principal at Control Risks...

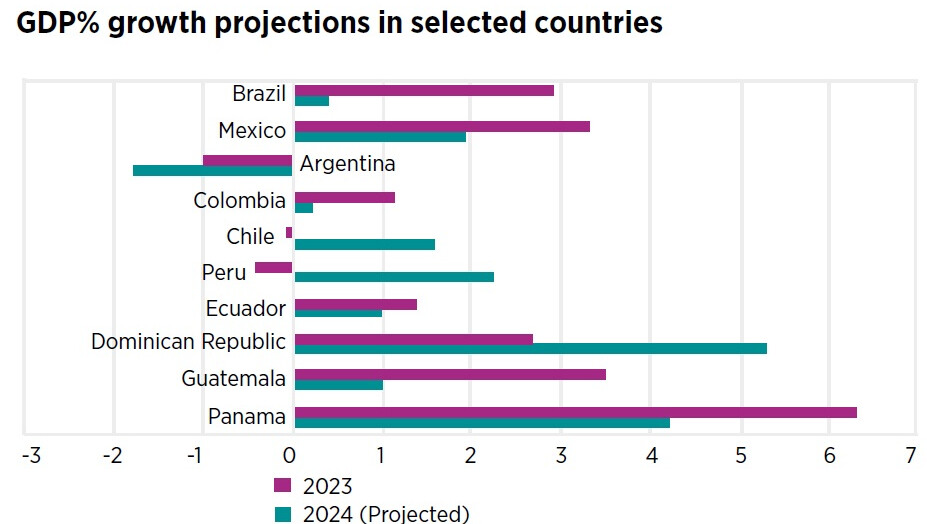

Latin America and the Caribbean (LatAm) enter the new year with a broadly stable economic outlook. The IMF expects the region to grow at 2.3% this year, just below the 2023 level. Inflation has mostly been brought under control (with Argentina and Venezuela the perennial exceptions proving the rule). Meanwhile, expectations that major central banks will begin lowering interest rates in the first half of the year will likely lead to more favourable financing conditions.

In this context, a prospective increase in M&A activity globally will spark further investor interest in the region, above all in strategic sectors such as agriculture, energy, infrastructure and technology. However, political risk—including a slate of critical elections, social conflict, and a complex and evolving geopolitical landscape—will continue to present challenges for companies and investors in 2024.

The year ahead

Undoubtedly, the general election of the year takes place in Mexico. The election will mark the end of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO)’s term in office but also more than likely result in the continuation of his ruling National Regeneration Movement (Morena) in power. Former Mexico City governor Claudia Sheinbaum (2018-23) – Morena’s candidate and AMLO’s designated successor – is a shoo-in to win and become Mexico’s first female president.

Before Mexicans go to the polls in June, there will be a trio of elections in the Caribbean basin, namely in El Salvador, Panama and the Dominican Republic. A general election will follow in Uruguay in October and a presidential poll is in the cards in Venezuela—where the recent loosening of US sanctions and warmongering against neighbouring Guyana have put the country in the international spotlight—though a date has yet to be confirmed.

In contrast to recent years, 2024 will be favourable for incumbents. Victories for Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele – the self-proclaimed “coolest dictator” in the world – and his Venezuelan counterpart Nicolás Maduro are all but guaranteed. In the case of the latter, the election result would be different if (and that is a big “if”) the election were free and fair. Meanwhile, a win for the ruling party candidate is likely in the Dominican Republic.

This is in keeping with a subregional trend that has seen incumbent parties and their candidates in the Caribbean – excluding the “mainland” Caribbean Community (Caricom) countries Belize, Guyana and Suriname – winning more often than not. This contrasts with what we’ve seen in LatAm as a whole in recent years.

Looking back

The more sanguine segments of the regional comentocracia have suggested that political alternation – exemplified by repeated election victories for the opposition – points to the strength and vibrancy of democracy in LatAm. But it is difficult to make that case in the context of the major elections in 2023. In Guatemala, anti-democratic forces are doing everything in their not-inconsiderable-power to prevent progressive president-elect Bernardo Arévalo’s inauguration on 14 January.

Political neophyte Daniel Noboa became Ecuador’s youngest president in an election marred by the assassination of one of the leading presidential candidates on the campaign trail. In Argentina, anti-establishment firebrand Javier Milei won amid widespread disillusionment with the country’s mainstream political parties (#ThatOldChestnut). Meanwhile, in Paraguay, the ruling Colorado (ANR) party candidate won despite – or perhaps because of – its poor track record on corruption and owing to the split in the opposition vote. 2023 was hardly an annus mirabilis for electoral democracy in LatAm.

Irrespective of the election results and the broader trends (real or imagined) behind them, incumbent and incoming administrations regionwide will face familiar governance challenges in 2024. These will include congressional gridlock, executive-legislative/executive-judicial conflict, civil unrest and politically disruptive insecurity. This in turn will hamstring their capacity to implement their policy platforms – including to promote the development of, and investment in, strategic sectors – deliver on campaign promises, and address their electorates’ myriad grievances. On the plus side, these dynamics should keep a lid on radicalism from both extremes of the political spectrum. Every cloud and all that…

Positive prognosis

The region will experience solid, but not spectacular, economic growth in 2024. A slowdown in the US and China and the accumulated impact of restrictive monetary policy (not to mention longer-term structural barriers) precludes a more bullish outlook. However, as ever with LatAm, there’s no one-size-fits-all economic forecast, particularly given that all countries face a multiplicity of sui generis drags on growth – including political instability, prolonged civil unrest and adverse weather conditions caused by climate change and/or El Niño.

Oxford Economics expects all major economies – except perennial basket case Argentina – to grow in 2024. Meanwhile, inflation will continue to cool: kudos to the region’s independent, inflation-busting central banks who scoffed at predictions that the pandemic-related price surge would be “transitory” and acted accordingly.

Looking up

FDI in LatAm skyrocketed in 2022 to its highest level on record. However, according to preliminary estimates, the FDI picture in 2023 was mixed, exemplified by the contrasting fortunes of regional powerhouses Mexico – where investment was on the up, driven by nearshoring – and Brazil (where it experienced a vertiginous drop partly due to investor concerns over currency risks and high borrowing costs).

In 2024, Brazil and the region more broadly are well placed to take advantage of an anticipated increase in M&A activity globally amid stabilising interest rates, continued efforts to strengthen supply chain resilience and industry consolidation. Control Risks expects considerable interest in cross-border and/or multijurisdictional deals in the agriculture, energy, infrastructure and technology sectors.

In demand

In 2024, LatAm will continue to attract the attention of investors, governments and multinational organizations. This in part reflects the region’s growing geopolitical importance – above all in the context of the US-China rivalry, regional conflicts that have had global implications (most notably, Ukraine-Russia and Israel-Hamas), the energy transition and ongoing efforts to strengthen supply chain resilience in strategic sectors following the pandemic.

It is no coincidence that the EU, India and Saudi Arabia, among others, have launched charm offensives in the region. However, China has stolen a march on all of them and its presence in LatAm will likely deepen in 2024, particularly as it continues to score points in its diplomatic zero-sum game with Taiwan.

Pretzel logic

In 2024, LatAm will benefit from the ever-evolving geopolitical situation. However, the region is not immune to geopolitical risk – contrary to what has been suggested in some quarters because of the policy of non-alignment pursued by many of its governments and its distance from conflict zones (current and possible). Venezuela’s bellicose attitude towards Guyana is a timely reminder that peace in LatAm cannot be taken for granted. Furthermore, geopolitics will continue to influence the US sanctions regime and Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) enforcement in LatAm, with adverse implications for companies and investors in the region. This will persist in 2024, as will the impact global developments have on domestic affairs (or vice versa).

The US presidential election in 2024 also looms large over the region. The so-called “Efecto Trump” in 2016 – whereby derogatory social media posts about Mexico (and Mexicans) by then-presidential candidate Donald Trump led to precipitous falls in the peso – serves as a warning sign as to what may happen this time around. Mexico is unlikely to be the only Latin American country used as a political football on the US campaign trail. Nevertheless, given everything that will happen in LatAm in 2024, this will be but water off a duck’s back.