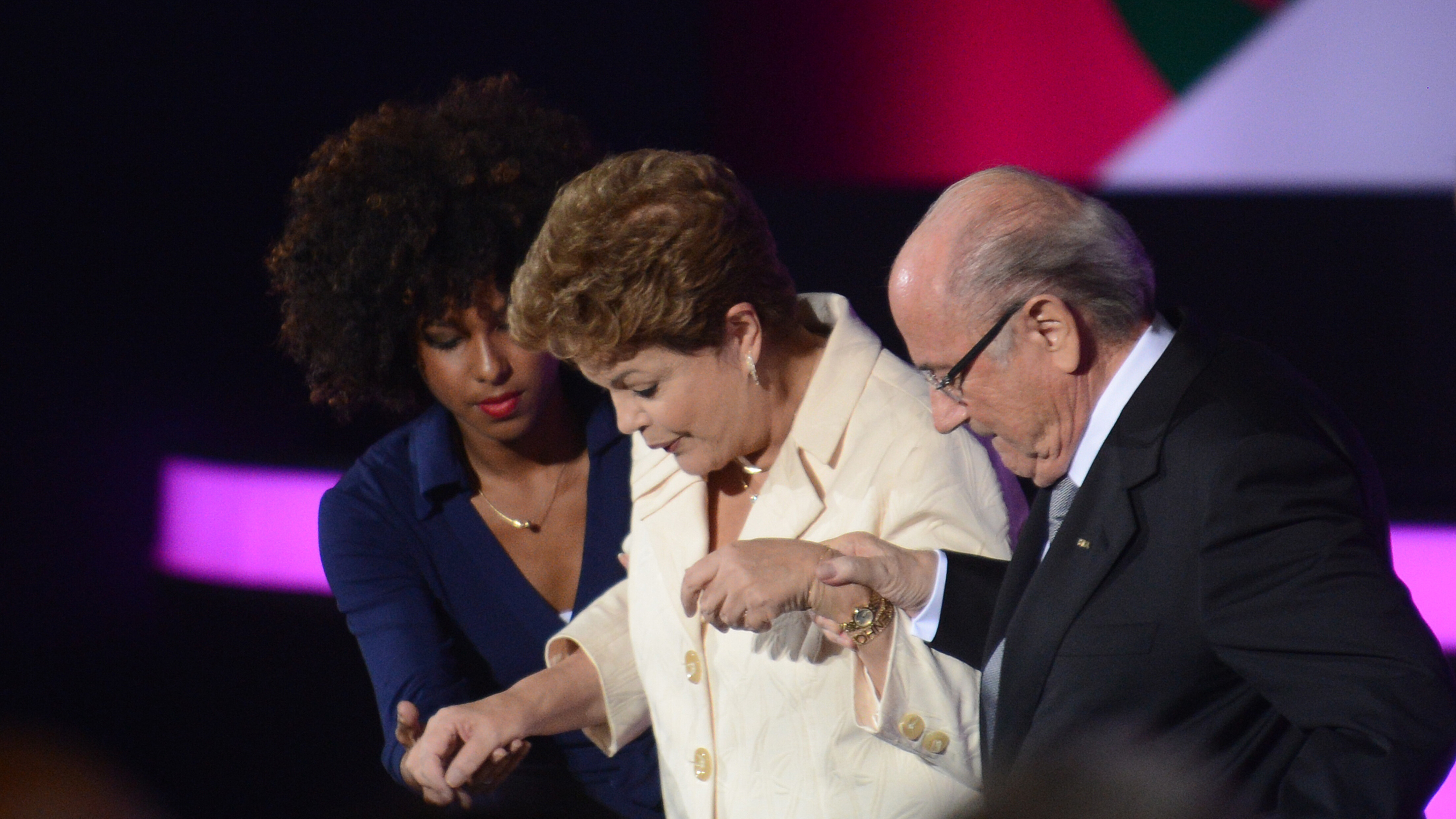

Rousseff Must Step Carefully

Latin America's biggest electorate has spoken and Brazil's incumbent, Dilma Rousseff, returns as president. Yet Holly Towner's review of the Brazilian press reaction to Rousseff's victory shows that the path ahead is far from simple...

Continuity or change?

Holly Towner

Dilma Rousseff, leader of the Worker’s Party, narrowly won against the centre-right, pro-market candidate, Aécio Neves, with 51.6% of the vote in the presidential election run-off at the end of October. Rousseff won a majority of votes in the North and North-East but failed to convince 48.6% of Brazilian voters, mainly in the more affluent south-eastern cities of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, that her government was capable of returning the Brazilian economy to its previous levels of growth as well as combating poor levels of investment, high inflation, a growing amount of public debt and the depreciation of the real.

“Rousseff’s election victory was sufficiently narrow to convince the President that almost half of Brazilian voters want change”, writes Luiz Sérgio Guimarães, in Brasil Econômico. “The result will force her to reassess her economic policy and realign herself with financial investors”, he says.

"There is only one way for Rousseff to calm the markets…"

Rousseff also faces intense pressure from markets for economic reform. Stock markets fell by 6% as trading reopened on the day after the election and “have failed to recover since the election campaign”, writes Fábio Alves, in the conservative newspaper, o Estado de São Paulo.

Difficult compromises

For Guimarães, “there is only one way for Dilma Rousseff to calm the markets”. She must “weave an alliance based on concessions on each side”. Since the election, Rousseff has tried to show that she is willing to cooperate with market interests. Speaking in an interview with the national news agency and media channel, O Globo, she pledged to combat inflation, to bring in tax reform to attract investors, and spoke openly of creating a “dialogue” with business and financial sectors, to discuss “potential courses for Brazil’s economy”.

Nevertheless, as Suely Caldas highlights in o Estado de São Paulo, two weeks after her election, a clear economic plan has still not been revealed by Rousseff. This has only resulted in “greater uncertainty among businessmen” over whether she is both serious about, and capable of, changing what her critics call her preference for “excessively” interventionist economic policies.

For Caldas, Rousseff’s delay in naming a successor to replace the current financial minister, Guido Mantega, who will step down at the end of the year, “is symptomatic of her indecisiveness”. Significantly, her choice of minister will provide a key indication of the direction Rousseff’s government is likely to take in the next four years as she tries to balance demands from her core supporters for greater income equality and pressure from business interests for a more market-friendly economy.

There are few signs to suggest that the next four years will be plain-sailing for Rousseff, nor that she will be able to do as she pleases. “Her narrow election victory will also make it more difficult for her to pass reform and will complicate her relationship with Congress”, writes Ranier Bragon in Folha de São Paulo. In the run-up to the elections, Rousseff made reform of the political system the central focus of her campaign. However, as Marco Antonio Teixeira points out in Estado de Minas, she will find it increasingly difficult to establish alliances in such a fragmented Congress as there will now be 28 parties instead of the 22 elected in 2010. In his article, Bragon sums up the unenviable reality of Rousseff’s political situation: “In 2015, the number of seats held by her supporters will be reduced from 338 seats to 304, four seats fewer than the actual number needed to approve constitutional reforms”.